18 Oct 2020

i was directed towards this scene from David Lynch’s 2001 film ‘Mulholland Drive’ by a commenter underneath the Father John Misty performance. the point of interest starts from about 1 minute in. i have not seen Mulholland Drive, but that fact did nothing to stop me from being undeniably perturbed by the performances at the ‘Club Silencio’. the audience in attendance are sparse and silent, so moving on from my last few blog post, i am instead focusing on the absence of performers, as suggested by the name of the venue. the host of the event in this scene repeats in a number of languages that everything we are watching is pre-recorded, and the sounds of the orchestra are all coming from speakers, digital files. a trumpeter demonstrates this by miming along to a solo before abandoning the facade and waving his instrument melodramatically. he is followed by a singer, who convincingly keeps up the already revealed gambit for longer, before collapsing on stage, her voice eerily surviving her presence as she is carried off by two stagehands. even though we know her performance is prerecorded, her collapse is no less shocking, and her powerful voice outlasting her is no less disconcerting. there’s not much i can really say about the scene apart from it feels wrong, and that it led me on to some other interesting ideas about the nature of performance, what we as an audience expect from performers, and the relationship between the seats and the stage.

lip-syncing or miming along to prerecorded music serves as an excellent and commonly debated baseline for the ‘absent’ performer and the ‘present’ audience. my flatmate drew my attention to the similarities between ‘Club Silencio’ and another scene in David Lynch’s ‘Blue Velvet’ (which this time i have seen, i promise), when Dean Stockwell’s immaculately dressed character, who has only just been introduced, mimes along to Roy Orbinson’s ballad ‘In Dreams’:

this is probably my favourite ever scene out of all the cinema i’ve watched (which, as you can probably tell, is not that much). its placement in the context of the film certainly heightens its effect: arriving around halfway though when the tensions between the banal and the absurd are finally released and all sense of normality and safety finally evaporate, this event acts as the pivot on which the film operates. but aside from that, we can view it independently as a layered performance, with differing and distinct audiences. Ben, stockwell’s character, is inexplicably dressed in georgian-era court dress, and is paled with the heavy make-up of the time. Already, this suggests an aura of facade, but one that he has adopted whole heartedly – as a performer he is not trying to trick the audience, just like the host of the Club Silencio, but instead adapts this fakery into the heart of his show. his microphone is a lamp, useless for amplifying his voice, but its presence gives him an air of authority, spotlighting his heavily made-up face. the tools of the performance are obviously fake, the lamp, the cassette player, the costume – but this means nothing – it is a strong performance nonetheless, one of the most affecting i’ve ever seen.

Within the film, there are two audiences: Frank (dennis hopper’s character), and the rest of the club house. There is a clear divide between the two, as made clear by the camera angles, with Frank placed next to Ben, often in the same shot, framed by the parted curtains – and the others, with the reverse of that shot. In the context of a theatre, Frank is on stage, and the others are in the stalls. This is reflected in their actions: Frank attentively watches Ben, firmly placing himself firmly within the audience, yet he identifies with the performer by standing on ‘stage’ and expressively lip-syncing along to the song, before becoming visibly repulsed by something and switching off the tape. Whereas the others are comfortable in their roles as spectators, subtly dancing or looking admirably towards Ben, Frank cannot assign himself to either position, tries to be both, and finally ends the show. He is missing Ben’s microphone (despite it’s being a lamp), costume, and captivating, unselfconscious air, yet he does have the power to turn it all off, which he does. This is the power of the participatory audience, a blunt demonstration of the pact between audience and performer, and what happens when you break it. when Ben briefly addresses his gaze and his ‘voice’ towards Frank, he is incorporated into the performance, but his presence in the audience is a necessity for the show – a dichotomy he apparently cannot bear.

but ! as previously stated, repeatedly, its all fake ! no one is ‘performing’ ! so how come both the Club Silencio and ‘In Dreams’ are so disarming? so powerful? so confusing? what does it even mean to perform? and what does it mean to watch a performance? and where is the boundary between the two? especially when the performer is merely an active audience member responding to a prerecorded performance by someone else? the power of the microphone can never be understated, even if it is never even plugged in.

all of this reminded me of a disconcertingly large world which i know almost nothing about: vocaloid. On a basic level, vocaloid is a software/digital synthesiser that accurately recreates the sound of a human voice. users of vocaloid can make electronic voices sing any tune, with any lyrics, in any context. the software comes in 2 different parts: the editor, in which voices are arranged and controlled, and the voices themselves. there are hundreds of different voices, mainly singing in japanese, with some chinese and less english, each with unique identities, names, costumes, personalities, backstories. vocaloid is just a software, like ableton or premier pro, but it’s users and fans have created an entire, populous and evolving narrative universe based on its sounds, as if each effect in premier pro was its own character. this dichotomy between product individuality / personality / independence, and complete user control is a little weird to me, but hasn’t stopped me from downloading the software and beginning to create tunes with the only free english voice i could find: ‘eleanor forte’. on its own, using vocaloid is a strange experience, and feels a little bit like playing god: i am at once both the audience and the performer, hearing my constructions sung back to me by an entity i control. but this dynamic is one that has proved to be extremely popular across the world.

hatsune miku was one of the first voices created for vocaloid, and has become something of a pop-star in her (?) own right, performing actual concerts (via hologram) across the globe to packed out audiences. in essence, miku is a vessel through which others, anyone really, can animate their own songs without relying on a voice, peskily attached to a real life human, with their own creative impulses and inflections. this hasn’t stopped her from becoming a personality in fans eyes, many of whom travel for hours to see her ‘perform’ (i don’t mean those quotation marks deridingly, i just mean to question what it really means to ‘perform’). like Ben, like the singer in Club Silencio, Hatsune Miku is obviously, unavoidably, openly fake – but the people still come, the performance is still affecting, the audience is still here. unlike other hologram performances, like tupac’s famous appearance at Coachella 15 years after his death, or, amusingly, a concert involving a real audience and a virtual Roy Orbison, the ‘In Dreams’ singer Ben channels in ‘Blue Velvet’, whose poster i recently saw in glasgow, miku’s concert goers are always aware of the ‘singer’s’ non-existence. she is not a reminiscence, or a recreation created to ease mourning or nostalgic tastes, she is what she is – a digital projection, a personality who doesn’t extend beyond the screen. her fans are also her creators, her audience her performers, she is a medium and an icon.

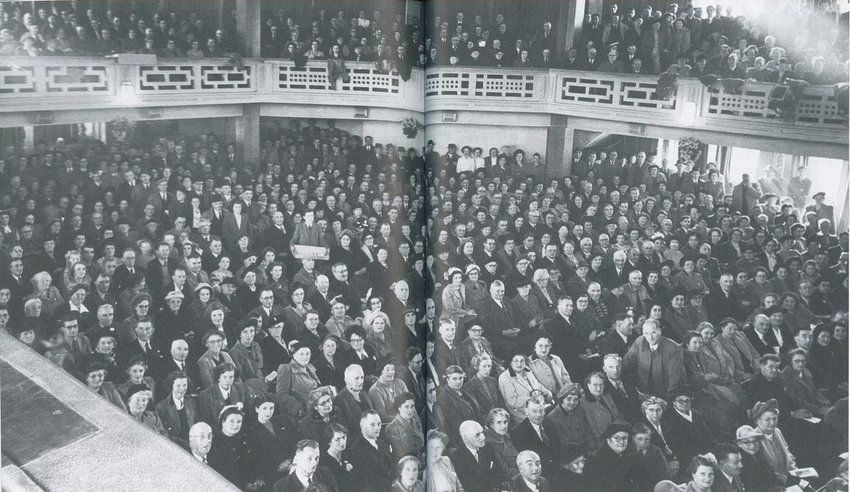

clearly, despite conventional notions, the presence of a performer is not always necessary. just as we have seen the audience be replaced (successfully or not) by prerecorded sound banks and robotic seat-fillers, the performer can be replaced by an image, real or digital, you decide. in an admittedly jarring jump, i’d like finally to look at one of this first instances of the phenomenon of the absent performer: Paul Robeson’s performance at the 1957 Porthcawl Miner’s eisteddfod. in what was probably one of the worlds first ‘live-streams’, and an event i’ve been fascinated with for a while now, Robeson performed over the phone from a studio in New York specifically for a packed hall of miners in Wales. he had a deep relationship with the Welsh miners union dating back years before the performance, and they had invited him to perform at their annual Eisteddfod, an offer which he gratefully accepted despite his relative stardom. There was one major problem – Robeson, after years of tension, had recently been blacklisted by the FBI for ‘communist activities’ and had had his passport taken away and his right to travel revoked. the miner’s union and Robeson came up with the ingenious idea of having him perform at the festival over the telephone: a crackly, virtual robeson performing through a rigged up speaker to a real crowd, eager just to hear his voice.

the crowd at the Eisteddfod

the result is beautiful. both Will Painter, the union leader, and Robeson’s addresses to the crowd are profound and clear, and robeson’s performance is powerful and strong despite his absence (you can listen to it all here)

the defining moment for me is when robeson is joined by the Treorchy Male Voice Choir for a rendition of ‘We’ll Keep A Welcome In The Hillside’, a song perfectly suited to the situation. as they sing, one disembodied voice over a telephone line united with a visible and physically present choral group, the crowd begin to join in – erasing all boundaries between performer and audience, an exercise in vocal solidarity resonating, literally, across continents.

the Porthcawl Eisteddfod differs vitally from the Club Silencio, ‘In Dreams’, and Hatsune Miku in that the image on stage is not what the focus is on. Robeson does ‘perform’ in a more traditional sense, and the effect is one of sincerity and genuine connection, rather than one of artifice and facade. but what unites the concerts of robeson and hatsune miku (a bizarre sentiment) is the audiences desire for a collective experience, no matter form the image on stage takes. as long as the performer stands for something which the crowd are invested in, the event always has the potential to be fulfilling for the audience and the performer. although everybody travels to ‘watch’ the act, the real sense of experience often comes from the feeling of being in a crowd, of watching a show with thousands of others, whose reactions, whether they mirror yours or not, are real and apparent even if the visuals are not. at the Eisteddfod, there is no tension between audience and performer, as in ‘Blue Velvet’, and as the boundaries are blurred, each individual associates themselves both with the spectator and the singer, and what emerges is an experience of heartfelt connection and grace. there may be no orchestra, as the host of the club silencio claims, but the power is still there.

16 Oct 2020

an obvious and contentious instance of the “fake crowd” is canned laughter, an inescapable feature of the pre-recorded comedy. canned laughter has an undeniable influence on how we interpret a scene or a joke, and sets a distinct, relaxed, and enthusiastic mood. it is uncritical, (ideally) comforting (although often not), encouraging and often aware of itself, referenced as an incorporated element of the sitcom format, like the set or the costumes, rather than an unmediated reaction to it. laughter, to certain types of comedy, is as inherent to the impact of the visual content as the crowd noises are to football, and watching back footage without it is often unsettling and confusing. although canned laughter is often derided as being painfully obvious and over-the-top (“no person in their right mind would ever audibly laugh at that joke”), it is undeniably essential to the enjoyment of some shows, which, with varying accuracy, do actually feel funnier with the added laughs. performances with participatory audiences, such as comedy or football, are dependant on a relationship, an exchange. they do not function in the same way as a concert or a lecture (in most cases, definitely debatable), in which the audience pays for a service, the performer provides them with it, and the audience leaves with new experiences or information (variations on which they could have gain asynchronously, distanced from the performer and the performance, in an online recording or a textual restructuring). obviously there is a lot to be said about being present at a performance, but on a very immediate surface level, audiences that participate, like comedy and football crowds, are more essential to the act of performance than those of other events. this is where it gets complicated: recreating these participatory reactions when a large, conscious, present audience is an impossibility. the inclusive alternatives all come with their drawbacks: virtual presence is unrewarding and often dull, with limited option for interaction; smaller, distanced crowds almost feel more depressing than an empty theatre and the participants are more self conscious as a result, the atmosphere sterile and stilted. the active, participatory crowd has never been so fragile, so why not just get rid of it?

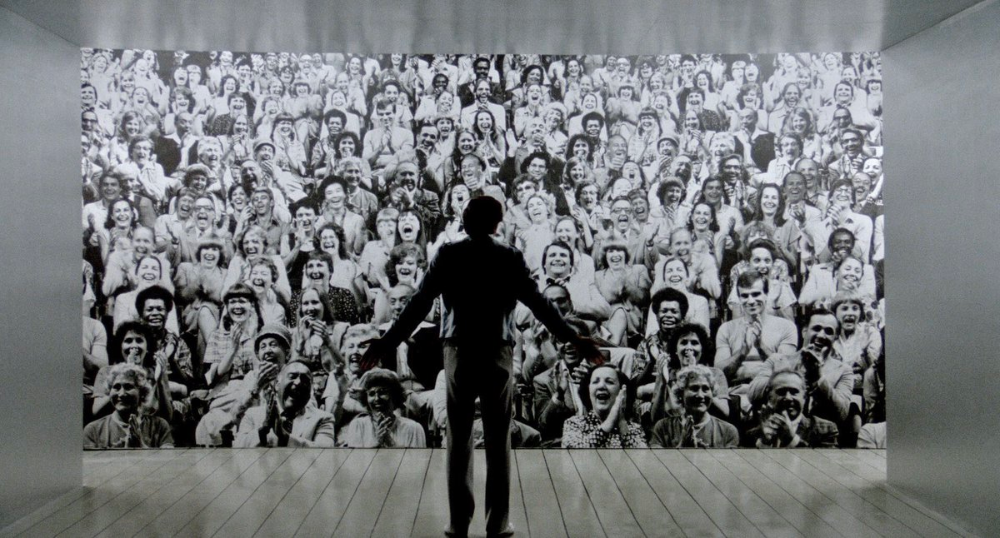

a still from ‘The King of Comedy’, a film which i have not seen.

those sorts of questions are the ones i was asking while investigating these new fake crowds at football matches, but i think that what i find the most interesting is what happens when the two separate audiences interact. in football this occurs with a large portion of viewers choosing to simply turn off the sound of their tv’s as they can’t bear the facile noises produced in vain by the scrambling broadcasters, whereas others swear by the effect on delivering a heightened moral to both players and fans. when the real is confronted by their digital replacement, who recoils?

in this performance from 2014, the singer/songwriter Father John Misty (Josh Tillman) plays his song ‘Bored In The USA’, which expresses sentiments of discontentment with the general gist of modern life. in the studio-recorded version of this song canned laughter and applause is digitally inserted in-between lines of the second verse, (“they gave me a useless education/And a subprime loan/On a craftsman home”). the lyrics are kind of funny, in a deprecating and defeatist way, but the canned laughter, ill-fitting and far fetched, only reinforces the mood of desperation and anger, rousing an eerie and tense effect. on the Letterman show, in front of a live audience, not necessarily familiar with his work, Tillman incorporates the canned laughter into his performance, and, as in the studio recording, laughs and claps respond to his last lines. the real audience, however, are unsure how to react, fearing that they are being contested by a second, participatory crowd who are privy to an unperceived layer of meaning. should they join in or abstain? slowly, once the performance has ended, traditional applause stutters up from the seated crowd, yet i wonder how many where moved to laugh as a result of the laugh-track? and how many were clapping out of direction rather than respect? we, as the audience at home, watching this back, who do we relate to? joining in the laughter – turning it on the unsuspecting live audience, or identifying with the confusion and dissociation they must have felt? the disembodied voices disrupt the atmosphere in an almost unresolvable way.

control over an unconscious, disconnected + digital hoard of voices creates an interesting dynamic in realms of entertainment in which the voices of the audience are omnipresent and understatedly powerful. however, when writing this i was reminded of this moment from the Jeb Bush 2016 presidential campaign, in which he exercises control over a crowd who are very much present, very much conscious, but decidedly (to him) not there:

when a performer has complete control over the instantaneous reactions of their audience, what point do the audience serve? they become a frame within a frame, packaging masquerading as reception which, in turn, affects the eventual reception itself. if the original, controlled audience are never given the choice to betray the performer, to act outside of the performer’s will, they don’t become obsolete, but act as a significant influence on the final, intended audience, who are often inclined to identify with the audience depicted in the media displayed (the fake football chants, the sitcom laugh track), directing them to a specified and outlined response. in the case of Jeb Bush, this illusion painfully falls apart. no matter how much investment a crowd may have in the image of the performer, complete control over them can never be achieved. inherently, with a live audience, we can’t have it both ways: a predictable and automated response comes at the expense of a genuine connection or exchange.

where fake crowd noise can be used to provoke an intended feeling from a real crowd if the context is congruous, it can also create a disarming effect when the content and reaction are at odds. this is apparent from the Father John Misty performance, just as it is in this youtube video entitled ‘if golf and soccer switched announcers’:

a year ago this video would have just been kinda funny, but now that audiences are a thing of the past – yet the show still goes on – there is a genuine space for these kinds of disorientations. the disappearance of the crowd has provided both a blank canvas and a new material in which all sorts of situations and combinations can be crafted. and, inversely, how could the absence of a conscious and variable crowd lead to all kinds of misdirection and manipulation?

(i can’t believe that that video is what lead me to make that point… nice

14 Oct 2020

been thinking about crowds for a long time – but was spurred on last night when i found this millwall chant:

football crowds have always been real interesting to me. unlike the audience of a concert or a play, the crowd are very much integral to the spectacle itself, and the sound of the crowd is, essentially, the sound track of the event. it is a participatory experience, with fans reacting in real time to the events on the pitch, as well as the events off of it, with an ever rotating and developing roster of chants and songs. i also like the idea of untrained mass singing, focusing just on the atmosphere and the overwhelming feel of the sound, rather than technical ability, which impresses in a very different, and much more immediate way.

this chant, whose history i am not qualified to assess, arose as a reaction to the media’s, and subsequently the public’s, perception of millwall as a club made exclusively of hooligan fans. something about the acceptance, incorporation and repurposing of this dire reputation by an audibly voluminous crowd is strangely powerful and decidedly unsettling. thousands of voices, fierce and deliberately antagonistic, summoned by the click of a button, and silenced again. where are these voices now?

since professional football has returned, teams have largely played to empty, eerily silent stadiums. a friend of mine (who knows a lot more about this world than i do) explained that clubs were starting to pump in sound through speakers arranged in the stands. it looks as if each club, and those in charge of their respective stadiums, have the ability to decide whether they want to install speaker systems or leave the pitch to the sounds of the players and managers. for the teams that have decided on having crowd noises implemented, where is this sound coming from? whose voices are substituting the thousands of missing bodies? who is in control of what they say? what they sing? and where do controversial chants such as millwall’s fit into this?

in an article from july (i am unsure as to how things have progressed since then) stadium managers at QPR explained how a company called Autograph developed a complex surround sound system to be installed in the stands. three engineers control individual sections of the stands, which react accordingly to events on the pitch (e.g. if an away defender is outpaced by the home teams right winger, the ghost fans at the right stand by the away goal will be heard cheering enthusiastically) and sing club chants. this bizarre video from the clubs twitter shows the setup in action:

when i say ‘bizarre’ i mean purely in effect: an empty stadium full of cheering fans. QPR’s efforts are certainly admirable, and sound a lot better than the less advanced alternatives of other clubs, or the Premier Leagues initial decision to simply add crowd noises in post- when the game is broadcast. however, seeing one man, reflected in the screen of his iPad, control an entire stadium of fans with the touch of a finger is certainly a strange and unsettling experience. interestingly, at the time when the article was written, QPR had lost all three of their home games with the surround sound system installed. i do wonder what the effect of an incredibly noisy, incredibly reactive, incredibly alive empty dead stadium is on the players’ mentality. do they feel the backing of a legion of supporters? or are their disembodied voices a mocking replica of the former adrenaline and glory?

to end on (for now), this line of thought reminded me of this horrific video of the audience of the Kelly Clarkson Show dancing to Vin Diesel’s new EDM song (from Stereogum):

this is disturbing, no doubt about it. but in a world where collective physical presence is no longer possible, what options do we have?

(not that. definitely not that. hopefully more on this to come)

edit 1: just found this video via a GQ article showing what happens when the audio engineers accidentally hit the wrong button in anticipation. watch from 15 seconds in:

edit 2: turns out the dystopia encroached upon in that Kelly Clarkson clip existed in South Korean baseball pre-pandemic, as early as 2014:

“Do not expect applause.” – W.S. Graham. Why not?